Puzzling over cell molecules

Students in the Master Lab learn how to conduct independent research in bio-signaling studies

Amelia Kutschera and Max Wiehl experience everyday work in the lab. Wilfried Weber (middle) provides support for the master students. Photo: Thomas Kunz

“When all of a sudden, they told me to design oligos so I could work out my plasmid, I thought, how do I go about that?” Max Wiehl knew about the ring-shaped pieces of DNA from lectures and practical courses, but now he was being told to draft, on his computer, a genetic sequence all by himself. “Usually we are given tasks in class with instructions and a clear outcome. But in the Master Lab I have to work it out for myself,” Wiehl explains. He believes that is the way to learn how to be a good researcher. In the first Master Lab at the CIBSS - Centre for Integrative Biological Signalling Studies, Wiehl and eleven other students from the Master's program in Biology, specializing in tri-national studies in biotechnology, practice how to work scientifically without assistance. They formulate their own questions, draft research plans and implement them - closely supervised by qualified researchers.

French and German tandems

Students had to apply in advance to get a place in the CIBSS Cluster of Excellence students program, which took place for the first time from June to December 2019. Three working groups from the fields of chemical and synthetic biology offer the participants an insight into research on molecular signals. Professor Maja Banks-Köhn, Professor Barbara Di Ventura and Professor Wilfried Weber each formed tandems of French and German students and gave them research challenges.

“We chose the ones we were interested in during the summer,” says Amelie Kutschera, who is researching a challenge on enzymes called phosphatases in Banks-Köhn's laboratory. The students have to integrate the proteins into a membrane. “We are developing a realistic in vitro system for this enzyme. To make it easier to research it, we insert it into a kind of vesicle,” Kutschera says, “This could one day help us to develop drugs to combat colon cancer.” She usually attends classes at the École Supérieure de Biotechnologie de Strasbourg (ESBS) at the University of Strasbourg in France. The French students come to Freiburg for two weeks in summer semester and five weeks in winter semester. “The universities pay for a hostel room for that time, using EUCOR network funding,” she adds.

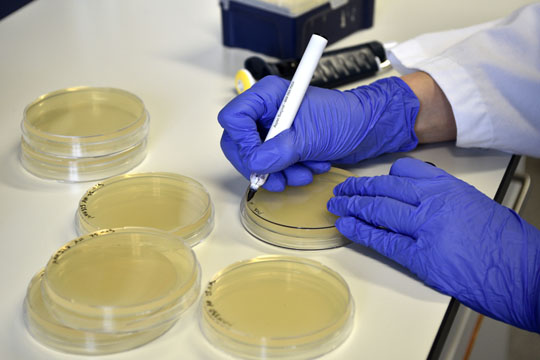

Taking notes: students learn how to independently design and carry out research projects. Photo: Thomas Kunz

Preparing for a Master's thesis

During the two-week summer session, the students decided on one of the challenges and began by drawing up a research plan. “This is how it often works at the beginning of a doctoral thesis,” says Dr. Hanna Wagner, coordinator of the Master Lab at CIBSS. “The program prepares students for what awaits them in their Master's thesis. And, if they want to do their doctorate, they have already made initial contacts and gained experience - and have already attended a conference.” Kutschera and Wiehl both went to a symposium in Heidelberg in the autumn. “We were the only students there. It was really something special,” says Kutschera, "very few people get a chance like that while they are still studying.” Over those four days, the two of them focused on getting to know the state of research in their field, exchanging ideas with doctoral students, and establishing contacts with researchers. They both say it was an important step on their future career path.

Putting plans into practice

General professional skills are included in the program; students write publications, give lectures, and learn time and project management in special units during the winter semester. They are also a part of the tasks they are given. “We had to draw up an exact schedule for our proposal and set milestones,” Wiehl says. His and Kutschera's research proposal was approved and they were able to start implementing their ideas in November. “This is an exciting phase for the students because they can now verify in practice whether their planning was likely to be successful,” says Wagner.

“This solving puzzles is what I enjoy most,” Amelie Kutschera says.

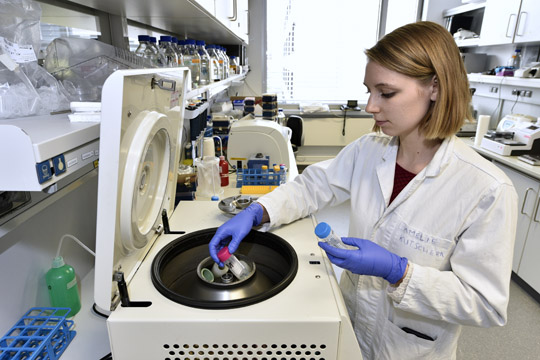

Photo: Thomas Kunz

They are working on their projects until the end of December. “Some of us want to tie it in with their Master's thesis,” says Wiehl. In his experiment in Weber's laboratory, Wiehl hopes to couple a protein which is responsible for the growth of cells and blood vessels, to a light-sensitive molecule. This technology, known as optogenetics, enables the protein to be switched on and off with blue light and thus can be used to precisely control cell growth. Further research in this field seeks to clarify the role of this protein in tumor development.

Finding new ideas and approaches

“This solving puzzles is what I enjoy most,” Kutschera says. The very first task in the Master lab presents a number of problems; once the challenge has been defined, the students have to read source literature, research techniques, grasp problems and suggest a possible solution. “Here you have to really immerse yourself in the material - think a lot more and connect a lot more than in my regular studies,” Kutschera stresses. Creativity is also called for, according to Wiehl. “The supervisors are very open to new ideas and approaches. We don’t know beforehand what the outcome of the project will be.”

Max Wiehl has four weeks to find out whether his solution for controlling cell growth is going to work. Photo: Thomas Kunz

That can mean that things go wrong and the students have to optimize their techniques or alter their plan. And that helps the Master lab students also learn how to find their way out of a dead end. “I am confident that the projects will be successful,” says Weber, “...maybe not with the solution as originally planned. But when I see how much commitment and creativity the students are developing in this project, I'm sure that they will see obstacles as a sporting challenge and will generate new ideas to overcome them.”

Wiehl's plasmids are now complete. With a little help from his supervisor, he now knows how to find the information he needs in databases and how to operate the computer program. He has designed and ordered the required short DNA pieces. At the end of this first project week, he is ready to slip on the lab coat and start the experiment. He has four weeks to find out whether his solution for controlling cell growth with light is going to work.

Mathilde Bessert-Nettelbeck